Fällgallrens sublima dån

Jag läser Luigi Russolos “Bullermanifest” – för vilken gång? – och känner som vanligt en behaglig rysning. Tänk ändå så tidig han var med sina idéer om att släppa ljuden fria. Ljudkonst, innan ljudkonsten ens var påtänkt.

Russolo skriver, full av entusiasm, om Oljudens konst redan 1913. Snart ska kriget driva honom i fält och utplåna alla framtidsplaner. Livet blir inte alls som Luigi tänkt sig utan han slutar som medioker akvarellmålare på marknaden i Laveno-Mombello.

Men kvar finns manifestet som han adresserar till kompositören Balilla Pratella, och som fortfarande kokar av så mycket inneboende potential.

My dear Balilla Pratella, great futurist musician,

On March 9, 1913, during our bloody victory over four thousand passé-ists in the Costanzi Theater of Rome, we were fist-and-cane-fighting in defense of your Futurist Music, performed by a powerful orchestra, when suddenly my intuitive mind conceived a new art that only your genius can create: the Art of Noises, logical consequence of your marvelous innovations. In antiquity, life was nothing but silence. Noise was really not born before the 19th century, with the advent of machinery.

Today noise reigns supreme over human sensibility. For several centuries, life went on silently, or mutedly. The loudest noises were neither intense, nor prolonged nor varied. In fact, nature is normally silent, except for storms, hurricanes, avalanches, cascades and some exceptional telluric movements. This is why man was thoroughly amazed by the first sounds he obtained out of a hole in reeds or a stretched string.

Primitive people attributed to sound a divine origin. It became surrounded with religious respect, and reserved for the priests, who thereby enriched their rites with a new mystery. Thus was developed the conception of sound as something apart, different from and independent of life. The result of this was music, a fantastic world superimposed upon reality, an inviolable and sacred world. This hieratic atmosphere was bound to slow down the progress of music, so the other arts forged ahead and bypassed it. The Greeks, with their musical theory mathematically determined by Pythagoras, according to which only some consonant intervals were admitted, have limited the domain of music until now and made almost impossible the harmony they were unaware of. In the Middle Ages music did progress through the development and modifications of the Greek tetracord system. But people kept considering sound only in its unfolding through time, a narrow conception so persistent that we still find it in the very complex polyphonies of the Flemish composers.

The chord did not yet exist; the development of the different parts was not subordinated to the chord that these parts could produce together; the conception of these parts was not vertical, but merely horizontal. The need for and the search for the simultaneous union of different sounds (that is to say of its complex, the chord), came gradually: the assonant common chord was followed by chords enriched with some random dissonances, to end up with the persistent and complicated dissonances of contemporary music.

First of all, musical art looked for the soft and limpid purity of sound. Then it amalgamated different sounds, intent upon caressing the ear with suave harmonies. Nowadays musical art aims at the shrilliest, strangest and most dissonant amalgams of sound. Thus we are approaching noise-sound. This revolution of music is paralleled by the increasing proliferation of machinery sharing in human labor. In the pounding atmosphere of great cities as well as in the formerly silent countryside, machines create today such a large number of varied noises that pure sound, with its littleness and its monotony, now fails to arouse any emotion.

To excite our sensibility, music has developed into a search for a more complex polyphony and a greater variety of instrumental tones and coloring. It has tried to obtain the most complex succession of dissonant chords, thus preparing the ground for Musical Noise.

This evolution toward noise-sound is only possible today. The ear of an eighteenth century man never could have withstood the discordant intensity of some of the chords produced by our orchestras (whose performers are three times as numerous); on the other hand our ears rejoice in it, for they are attuned to modern life, rich in all sorts of noises. But our ears far from being satisfied, keep asking for bigger acoustic sensations. However, musical sound is too restricted in the variety and the quality of its tones.

The most complicated orchestra can be reduced to four or five categories of instruments with different sound tones: rubbed string instruments, pinched string instruments, metallic wind instruments, wooden wind instruments, and percussion instruments. Music marks time in this small circle and vainly tries to create a new variety of tones. We must break at all cost from this restrictive circle of pure sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.

Each sound carries with it a nucleus of foreknown and foregone sensations predisposing the auditor to boredom, in spite of all the efforts of innovating composers. All of us have liked and enjoyed the harmonies of the great masters. For years, Beethoven and Wagner have deliciously shaken our hearts. Now we are fed up with them. This is why we get infinitely more pleasure imagining combinations of the sounds of trolleys, autos and other vehicles, and loud crowds, than listening once more, for instance, to the heroic or pastoral symphonies.

It is hardly possible to consider the enormous mobilization of energy that a modern orchestra represents without concluding that the acoustic results are pitiful. Is there any, thing more ridiculous in the world than twenty men slaving to increase the plaintive meeowing of violins? This plain talk will make all music maniacs jump in their seats, which will stir up a bit the somnolent atmosphere of concert halls. Shall we visit one of them together? Let’s go inside one of these hospitals for anemic sounds. See, the first bar is dripping with boredom stemming from familiarity, and gives you a foretaste of the boredom that will drip from the next bar. In this fashion we sip from bar to bar two or three sorts of boredom and keep waiting for the extraordinary sensation that will never materialize. Meanwhile we witness the brewing of a heartrending mixture composed of the monotony of the sensations and the stupid and religious swooning of the audience, drunk on experiencing for the thousandth time, with almost Bhuddist patience, with elegant and fashionable ecstasy. POUAH!

Let’s get out quickly, for I can’t repress much longer the intense desire to create a true musical reality finally by distributing big loud slaps right and left, stepping and pushing over violins and pianos, bassoons and moaning organs! Let’s go out!

Some will object that noise is necessarily unpleasant to the ear. The objection is futile, and I don’t intend to refute it, to enumerate all the delicate noises that give pleasant sensations. To convince you of the surprising variety of noises, I will mention thunder, wind, cascades, rivers, streams, leaves, a horse trotting away, the starts and jumps of a carriage on the pavement, the white solemn breathing of a city at night, all the noises made by feline and domestic animals and all those man’s mouth can make without talking or singing.

Let’s walk together through a great modern capital, with the ear more attentive than the eye, and we will vary the pleasures of our sensibilities by distinguishing among the gurglings of water, air and gas inside metallic pipes, the rumblings and rattlings of engines breathing with obvious animal spirits, the rising and falling of pistons, the stridency of mechanical saws, the loud jumping of trolleys on their rails, the snapping of whips, the whipping of flags. We will have fun imagining our orchestration of department stores’ sliding doors, the hubbub of the crowds, the different roars of railroad stations, iron foundries, textile mills, printing houses, power plants and subways. And we must not forget the very new noises of Modern Warfare.

We want to score and regulate harmonically and rhythmically these most varied noises. Not that we want to destroy the movements and irregular vibrations (of tempo and intensity) of these noises! We wish simply to fix the degree or pitch of the predominant vibration, as noise differs from other sound in its irregular and confuse vibrations (in terms of tempo and intensity).

Each noise possesses a pitch, at times even a chord dominating over the whole of these irregular vibrations. The existence of this predominant pitch offers us the technical means of scoring these noises, that is to say to give to a noise a certain variety of pitches without losing the timbre that characterizes and distinguishes it. Certain noises obtained through a rotating movement can give us a complete ascending or descending scale through the speeding up or slowing down of he movement.

Noise accompanies every manifestation of our life. Noise is familiar to us. Noise has the power to bring us back to life. On the other hand, sound, foreign to life, always a musical, outside thing, an occasional element, has come to strike our ears no more than an overly familiar face does our eye.

Noise, gushing confusely and irregularly out of life, is never totally revealed to us and it keeps in store innumerable surprises for our benefit. We feel certain that in selecting and coordinating all noises we will enrich men with a voluptuousness they did not suspect. Although the characteristic of noise is to brutally bring us back to life, the art of noises must not be limited to a mere imitative reproduction.

1 – We must enlarge and enrich more and more the domain of musical sounds. Our sensibility requires it. In fact it can be noticed that all contemporary composers of genius tend to stress the most complex dissonances. Moving away from pure sound, they nearly reach noise-sound. This need and this tendency can be totally realized only through the joining and substituting of noises to and for musical sounds.

2 – We must replace the limited variety of timbres of orchestral instruments by the infinite variety of timbres of noises obtained through special mechanisms.

3 – The musician’s sensibility, once he is rid of facile, traditional rhythms, will find in the domain of noises the means of development and renewal, an easy task, since each noise offers us the union of the most diverse rhythms as well as itsdominant one.

4 – Each noise possesses among its irregular vibrations a predominant basic pitch. This will make it easy to obtain, while building instruments meant to produce this sound, a very wide variety of pitches, half-pitches and quarter-pitches. This variety of pitches will not deprive each noise of its characteristic timbre but, rather, increase its range.

5 – The technical difficulties presented by the construction of these instruments are not grave. As soon as we will have found the mechanical principle which produces a certain noise, we will be able to graduate its pitch according to the laws of acoustics. For instance, if the instrument employs a rotating movement, we will speed it up or slow it down. When not dealing with a rotating instrument we will increase or decrease the size or the tension of the sound-making parts.

6 – This new orchestra will produce the most complex and newest sonic emotions, not through a succession of imitative noises reproducing life, but rather through a fantastic association of these varied sounds. For this reason, every instrument must make possible the changing of pitches through a built-in.

7 – The variety of noises is infinite. We certainly possess nowadays over a thousand different machines, among whose thousand different noises we can distinguish. With the endless multiplication of machinery, one day we will be able to distinguish among ten, twenty or thirty thousand different noises. We will not have to imitate these noises but rather to combine them according to our artistic fantasy.

8 – We invite all the truly gifted and bold young musicians to analyze all noises so as to understand their different composing rhythms, their main and their secondary pitches. Comparing these noise sounds to other sounds they will realize how the latter are more varied than the former. Thus the comprehension, the taste, and the passion for noises will be developed. Our expanded sensibility will gain futurist ears as it already has futurist eyes. In a few years, the engines of our industrial cities will be skillfully tuned so that every factory is turned into an intoxicating orchestra of noises.

My dear Pratella, I submit to your futurist genius these new ideas, and I invite you to discuss them with me. I am not a musician, so that I have no acoustic preferences, nor works to defend. I am a futurist painter who projects on a profoundly loved art his will to renew everything. This is why, bolder than the bolder professional musician, totally unpreoccupied with my apparent incompetence, knowing that audacity gives all prerogatives and all possibilities, I have conceived the renovation of music through the Art of Noise.

Luigi Russolo, Painter, Milano, March 11, 1913. Direction of the futurist movement: Corso Venezia, 61, Milano.

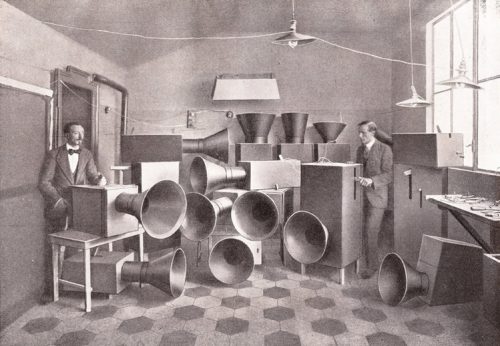

Luigi Russolo (till vänster) och hans bullerinstrument Intonatorium

MS